Renée Stout is yet again radically reinventing herself.

Over the course of her career, the sculptor has invented whole new identities with which to create her voodoo art: a rootworker named Dorothy; a mystic named Madame Ching; an herbalist named Fatima Mayfield. Her work has always drawn deeply from the Caribbean corner of the African diaspora, even as she herself has flitted from one persona to another, forward and backward through time and across continents.

Her latest exhibition at Hemphill Fine Arts takes the viewer to what might be an alternate dimension entirely. “Wild World,” the artist’s fifth solo show at Hemphill, envisions a steampunk universe that—bear with me—has nothing to do with Jules Verne, H.G. Wells, polished brass, or even Europe for that matter. Stout’s found a portal to a place that blends hoodoo and Santería with gadgets and gizmos.

A mixed-media sculpture called “Crossroads Transmitter” summons a vision of a creole Nikola Tesla. It’s easy to imagine one of Stout’s characters, her Lady Fatima, hunched over this device, working various knobs to tune into other-worldly frequencies. This piece and others—“Spirit Selector,” “Haunted Machine,” “Spirit Detector”—look like old-timey radios, built out of loop antennae, analog meters, and glass tubes. Many of these are found parts; Stout is a magpie, a collector. But the works are unmistakably sculptural, not merely vintage.

“Soul Catcher/Regenerator” is a nightstand-sized contraption paired with some kind of mannequin in a cage. Made to look as if it were discovered in an auntie’s attic, the piece is both familiar and strange, a testament to Stout’s craft. “Soul Catcher/Regenerator” reverberates across epochs. The piece is a nod to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and the birth of genre; yet the pair also resemble a kind of Afro-goth C-3PO and R2-D2. Threepio himself is an anachronistic amalgamation, a fussy clockwork butler built in the mold of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis—but nevermind him. The point is that Stout’s work, and especially “Soul Catcher/Regenerator,” teases at a universe as immersive as Star Wars, but one infused with the energy of tropicalia from Brazil or Négritude from France.

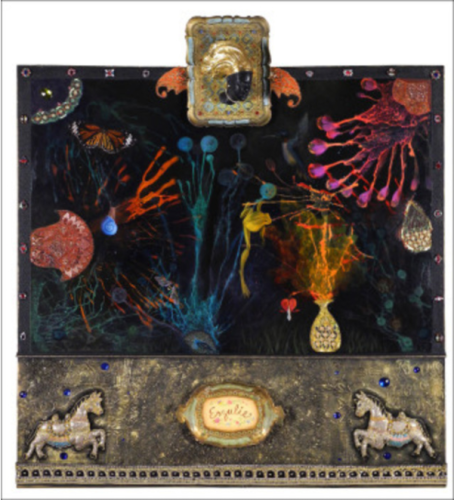

Stout’s work is plenty contemporary, too. In most of her shows, she’s explored her fascination with botánicas, usually by displaying the artifacts that they sell: bottles of herbs, minerals, and teeth for spells, for example, or candles with different mystical properties. (After nearly 20 years, Adams Morgan’s Botánica Yemaya & Chango closed in April 2014.) This time, for “Wild World,” Stout offers several paintings of the neon signs that typically grace these spiritual sundry shops—and they work like edgy Pop Art exercises. “High John Root” and “Readings” might be Stout’s take on Ed Ruscha or Andy Warhol. Meanwhile, a wall assembly of voodoo-tech (“Lay Your Hands on the Radio”) summons the spirit of Louise Nevelson to the viewer’s side, like a sculptural séance.

There’s a lot to look at in “Wild World,” and that’s the show’s one big drawback: Fewer things might make Stout’s vision more mysterious, and more urgent. Works like “The Pearl Gourd” (an echo of Martin Puryear’s “Old Mole,” maybe) have a place in some show—many shows—but not this show. An editor might strike a half-dozen collages and paintings, plus a sculpture or two. One piece that stays is “Crossroads Diagram,” an unexpected drawing for Stout: precise, geometric, artificial-looking. The drawing seems to indicate that there are limits to the world of man. For all its precision and possibility, a machine is a clunky tool for fetching souls.

Diaspora histories are often unofficial, told through tradition. Somehow, Stout manages to convey a sense of oral history through a few careful objects. It’s not just that these summoning devices look old and lost and weathered. It looks like their users operated under the cover of darkness, in servant quarters, far from watchful eyes; working with a mix of dread and love, fear and hope, for what might happen; blending root magic with Western industry, a corruption, no, a necessity—I get carried away. This show gives me goose bumps.