Washington abstractionist Howard Mehring lived for a mere 47 years, and his career was much shorter than that. His major work was made in a period that lasted barely a decade. “Mehring/Wellspring: The Early Color Field Paintings of Howard Mehring” covers only about half that time, and most of the pictures in the retrospective at the American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center date from just 1958 to 1960.

The painting that stands out does so by being uncharacteristic. “Spring Thaw” is an active volcano of mostly bright hues, dominated by a thick orange gush offset by a thin black vein. The picture reveals the influence of both Jackson Pollock, emperor of New York abstract expressionism, and Morris Louis, the dean of Washington’s Color School.

Like the much more celebrated Louis, Mehring was a D.C. colorist who died young and whose technique remains somewhat mysterious. But while Louis was still working at the time of his 1962 death, Mehring abandoned painting a decade before his fatal 1978 heart attack. Mehring had continued to draw, and friends and colleagues differ on whether his switch to drawing was a transition or a surrender.

“He went to pieces,” said fellow local artist Jacob Kainen, according to an essay in the show’s catalogue by onetime National Gallery of Art curator E.A. Carmean Jr.

“Some say his nerve had failed. I don’t think so,” is Carmean’s own judgment.

The drama of Mehring’s renunciation of painting is not pertinent to this selection. Before quitting, the artist was making hard-edge geometric pictures with bolder colors, and these are probably his best-known works. But they’re less distinctive than the earlier canvasses surveyed here.

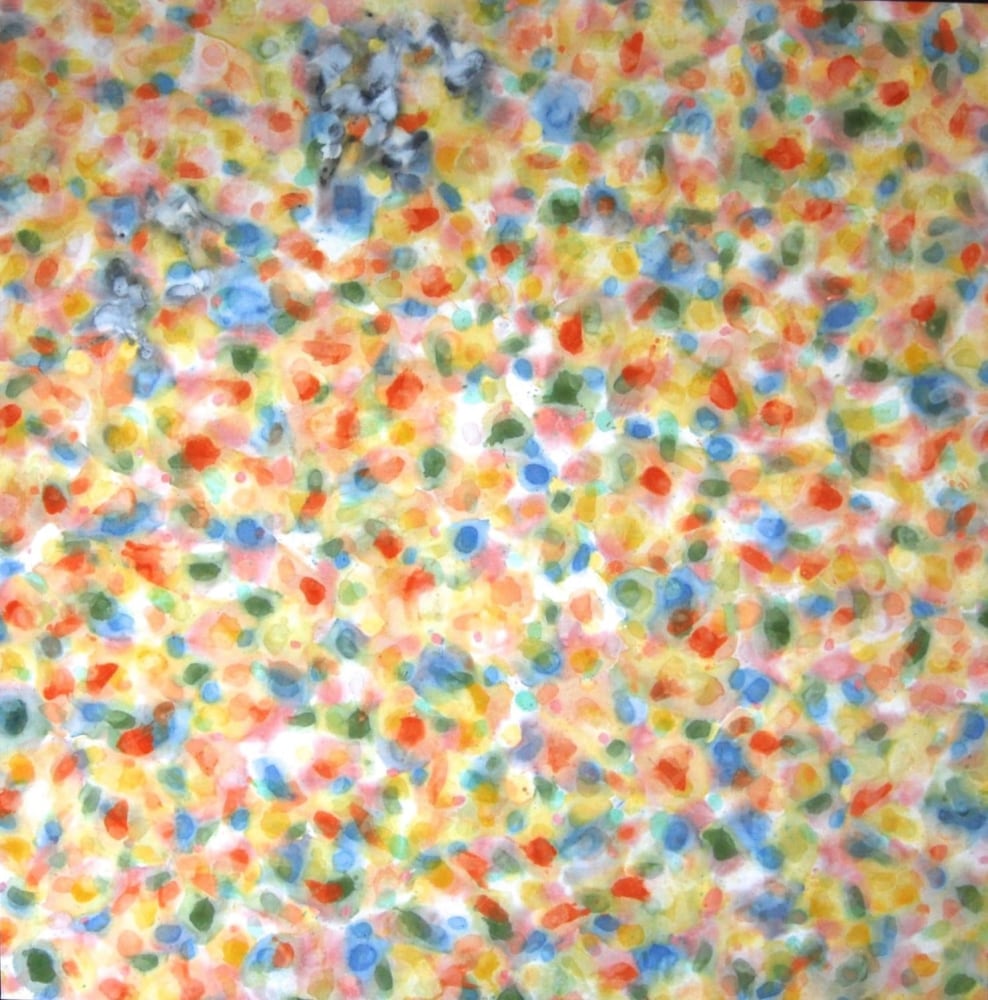

With the exception of “Spring Thaw,” they’re “allover” paintings that lack Louis’s compositional structures or Pollock’s sense of motion. What they do have is an enveloping, immersive power. “I want the surface of my paintings to breathe and to breathe color so that I am able to look into the painting and penetrate it visually,” Mehring told Washington art chronicler Mary Swift.

The prettier pictures employ pastel and floral hues, dotted on the fabric densely, but with enough white space to distinguish each one. The link to French Impressionism, particularly Monet and Seurat, is apparent. Mehring could evoke springtime without depicting natural forms.

Like the other local colorists of the era — most of whom he knew well — Mehring used the then-new acrylic pigments, diluted so they had a fluid quality while retaining vivid hues. He and the others employed unprimed canvas into which the pigment seeped. The style was deemed “post-painterly” by Clement Greenberg, the New York critic who boosted (and sometimes guided) the artists. Paint was poured and splashed more often than brushed. Mehring’s method is unknown, although Kainen believes he used sponges.

Of the paintings in this show, many are coolly minimalist and carefully confined to a single color range. Several suggest the patterning of marble or other stone, and one predominantly gray canvas barely emerges from the gray wall on which it’s hung. But others use bolder hues, sometimes submerged into black. On closer inspection, these large pictures are much livelier than they appear from a distance.

The Washington Color School is still much discussed in the D.C. art world — some might say too much so — and the artists are enjoying a posthumous commercial boom at galleries here and elsewhere. Hemphill Fine Arts is showing work by four local 20th-century colorists: Alma Thomas, Tom Downing, Paul Reed and Mehring. (The three Mehring paintings include examples of his allover and geometric work.) And the Smithsonian American Art Museum has filled a large gallery with exhilarating stripe paintings by Gene Davis, another of the loosely aligned group.

Mehring, Davis and Reed were born and raised in Washington and spent most of their lives here. In fact, they went to the same high school, McKinley. If that makes the Color School sound like a small-town phenomenon, in some ways it was. Yet its best work was expansive. To gaze into the paint-dotted expanses of “Mehring/Wellspring” is to enter a universe of subtle gestures and dappled color.